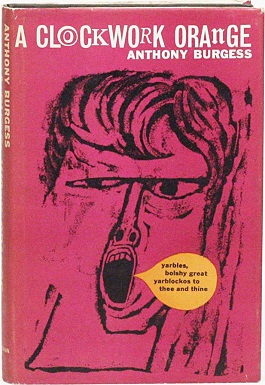

A Clockwork Orange, Anthony Burgess

The Stanley Kubrick-directed film adaptation of the novel (to be fair, not the novel itself — but the movie does stay fairly faithful to the text) reportedly inspired several copycat crimes in Britain in the years following its release. In one 1972 case of a sixteen year old boy killing a fourteen year old classmate, the killer admitted that his friends had told him about the film, and the defense claimed that “the link between this crime and sensational literature, particularly A Clockwork Orange, is established beyond reasonable doubt”. In another case, a group of youths attacked a teenage girl and sang “Singin’ in the Rain” while they raped her — in the film Alex sings the same tune while preparing a similar crime. However, as far as we can recall, there’s no mention of this detail in the novel.

==========================================================

==========================================================

A Clockwork Orange is a 1962 dystopian novella by Anthony Burgess. The novel contains an experiment in language: the characters often use an argot called "Nadsat", derived from Russian. In 1998, the Modern Library ranked A Clockwork Orange 65th on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century.

|

[edit]Plot summary

[edit]Part 1: Alex's world

Alex, a teenager living in near-future England, leads his gang on nightly orgies of opportunistic, random "ultra-violence." Alex's friends ("droogs" in the novel's Anglo-Russian slang, Nadsat) are Dim, a slow-witted bruiser who is the gang's muscle; Georgie, an ambitious second-in-command; and Pete, who mostly plays along as the droogs indulge their taste for ultra-violence. Alex is characterized as a sociopath and a hardened juvenile delinquent; he is nonetheless intelligent and quick-witted, with sophisticated taste in music. He is particularly fond of Beethoven, or "Lovely Ludwig Van."

The novel begins with the droogs sitting in their favorite hangout, drinking milk-drug cocktails, called "milk-plus", to hype themselves for the night's mayhem. They assault a scholar walking home from the library, stomp a panhandling derelict, scuffle with a rival gang, then rob a newsstand and leave its owners bloodied and unconscious. Joyriding through the countryside in a stolen car, they break into an isolated cottage and maul the young couple living there, beating the husband and raping his wife. In a metafictional touch, the husband is a writer working on a manuscript called "A Clockwork Orange," and Alex contemptuously reads out a paragraph that states the novel's main theme before shredding the manuscript. Back at the milk bar, Alex punishes Dim for some crude behaviour, and strains within the gang become apparent. At home in his dreary flat, Alex plays classical music at top volume while fantasizing of even more orgiastic violence.

Alex skips school the next day. Following an unexpected visit from P.R. Deltoid, his "post-corrective advisor," Alex meets a pair of ten year old girls and takes them back to his parents' flat, where he administers hard drugs and then rapes them. That evening, Alex finds his droogs in a mutinous mood. Georgie challenges Alex for leadership of the gang, demanding that they pull a "man-sized" job. Alex quells the rebellion by slashing Dim's hand and fighting with Georgie, then in a show of generosity takes them to a bar, where Alex insists on following through on Georgie's idea to burgle the home of a wealthy old woman. The break-in starts as farce and ends in tragic pathos, as Alex's attack kills the elderly woman. His escape is blocked by Dim, who attacks Alex, leaving him disabled on the front step as the police arrive.

[edit]Part 2: The Ludovico Technique

Sentenced to prison for murder, Alex works in the prison library and gets taken under the wing of the prison chaplain, who mistakes Alex's Bible studies for stirrings of faith (Alex is actually reading Scripture for the violent passages). After Alex is blamed for beating a troublesome cellmate to death by his fellow cellmates, he is accepted into an experimental behaviour-modification treatment called the Ludovico Technique. The technique is a form of aversion therapy in which Alex is injected with a drug that makes him feel sick and is forced to watch graphically violent films, eventually conditioning him to suffer crippling bouts of nausea at the mere thought of violence. As an unintended consequence, the soundtrack to one of the films—Beethoven's Ninth Symphony—renders Alex unable to listen to his beloved classical music.

The effectiveness of the technique is demonstrated to a group of VIPs, who watch as Alex collapses before a walloping bully, and abases himself before a scantily-clad young woman whose presence has aroused his predatory sexual inclinations. Though the prison chaplain accuses the state of stripping Alex of free will, the government officials on the scene are pleased with the results and Alex is released into society.

[edit]Part 3: After prison

Barred from returning home (his parents are now renting his room to a lodger), the defenseless Alex wanders the streets and accidentally encounters his former victims, all of whom are keen on revenge. The policemen who come to Alex's rescue turn out to be none other than Dim and former gang rival Billyboy. The two policemen promptly beat Alex. Dazed and bloodied, Alex collapses at the door of an isolated cottage, realizing too late that it is the house he and his droogs invaded in the first half of the story. Because the gang wore masks during the assault, the writer does not immediately recognize Alex. The writer, whose name is revealed as F. Alexander, shelters Alex and questions him about the conditioning. During this sequence, it is revealed that Mrs. Alexander died from the injuries inflicted during the gang-rape, and her husband has decided to continue living "where her fragrant memory persists" despite the horrid memories. Though Alexander, a critic of the government, hopes to use Alex as a symbol of state brutality and thereby prevent the incumbent government from being re-elected, he begins to realize Alex's role in the happenings of the night two years ago. One of Alexander's radical associates manages to extract a confession from Alex after removing him from F. Alexander's home and lock him in a flatblock near his former home. Alex is then subjected to a relentless barrage of classical music, prompting him to attempt suicide by leaping from a high window.

Alex wakes up in hospital, where he is courted by government officials anxious to counter the bad publicity created by his suicide attempt. With Alexander safely packed off to a mental institution, Alex is offered a well-paying job if he agrees to side with the government. As photographers snap pictures, Alex daydreams of orgiastic violence and realizes the Ludovico conditioning has been reversed: "I was cured all right."

In the final chapter, Alex has a new trio of droogs, but he finds he is beginning to outgrow his taste for violence. A chance encounter with Pete, now married and settled down, inspires Alex to seek a wife and family of his own. He contemplates the likelihood of his future son being a delinquent as he was, a prospect Alex views fatalistically.

[edit]Omission of the final chapter

The book has three parts, each with seven chapters. Burgess has stated that the total of 21 chapters was an intentional nod to the age of 21 being recognised as a milestone in human maturation. The 21st chapter was omitted from the editions published in the United States prior to 1986.[1] In the introduction to the updated American text (these newer editions include the missing 21st chapter), Burgess explains that when he first brought the book to an American publisher, he was told that U.S. audiences would never go for the final chapter, in which Alex sees the error of his ways, decides he has lost all energy for and thrill from violence and resolves to turn his life around (a slow-ripening but classic moment of metanoia—the moment at which one's protagonist realises that everything he thought he knew was wrong).

At the American publisher's insistence, Burgess allowed their editors to cut the redeeming final chapter from the U.S. version, so that the tale would end on a darker note, with Alex succumbing to his violent, reckless nature—an ending which the publisher insisted would be 'more realistic' and appealing to a U.S. audience. The film adaptation, directed by Stanley Kubrick, is based on the American edition of the book (which Burgess considered to be "badly flawed"). Kubrick called Chapter 21 "an extra chapter" and claimed[2] that he had not read the original version until he had virtually finished the screenplay, and that he had never given serious consideration to using it. In Kubrick's opinion, the final chapter was unconvincing and inconsistent with the book.

[edit]Characters

- Alex: The novel's anti-hero and leader among his droogs. He often refers to himself as "Your Humble Narrator." (Having seduced two girls in a music shop, Alex refers to himself as "Alexander the Large" while ravishing them; this was later the basis for Alex's claimed surname DeLarge in the 1971 film.)

- George or Georgie: Effectively Alex's greedy second-in-command. Georgie attempts to undermine Alex's status as leader of the gang. He later dies from a botched robbery attempt during Alex's stay in prison.

- Pete: The most rational and least violent member of the gang. He is the only one who doesn't take particular sides when the droogs fight among themselves. He later meets and marries a girl, renouncing his old ways and even losing his former speech patterns. A chance encounter with Pete in the final chapter influences Alex's wishes to reform and become a productive member of society.

- Dim: An idiotic and thoroughly gormless member of the gang, persistently condescended to by Alex, but respected to some extent by his droogs for his formidable fighting abilities, his weapon of choice being a length of bike chain. He later becomes a police officer, exacting his revenge on Alex for the abuse he once suffered under his command.

- P. R. Deltoid: A criminal rehabilitation social worker assigned the task of keeping Alex on the straight and narrow. He seemingly has no clue about dealing with young people, and is devoid of empathy or understanding for his troublesome charge. Indeed, when Alex is arrested for murdering an old woman, and then ferociously beaten by several police officers, Deltoid simply spits on him.

- The prison chaplain: The character who first questions whether it's moral to turn a violent person into a behavioural automaton who can make no choice in such matters. This is the only character who is truly concerned about Alex's welfare; he is not taken seriously by Alex, though. (He is nicknamed by Alex "prison charlie" or "chaplin," an allusion to Charlie Chaplin.)

- Billyboy: A rival of Alex's. Early on in the story, Alex and his droogs battle Billyboy and his droogs, which ends abruptly when the police arrive. Later, after Alex is released from prison, Billyboy (along with Dim, who like Billyboy has become a police officer) rescue Alex from a mob, then subsequently beat him, in a location out of town.

- The governor: The man who decides to let Alex "choose" to be the first reformed by the Ludovico technique.

- Dr. Branom: Brodsky's colleague and co-founder of the Ludovico technique. He appears friendly and almost paternal towards Alex at first, before forcing him into the theatre and what Alex calls the "chair of torture."

- Dr. Brosky: The scientist and co-founder of the "Ludovico technique." He seems much more passive than Branom, and says considerably less.

- F. Alexander: An author who was in the process of typing his magnum opus A Clockwork Orange, when Alex and his droogs broke into his house, beat him, tore up his work, and then brutally gang raped his wife, which caused her subsequent death. He is left deeply scarred by these events, and when he encounters Alex two years later he uses him as a guinea pig in a sadistic experiment intended to prove the Ludovico technique unsound.

- Cat Woman: An indirectly-named woman who blocks Alex's gang's entrance scheme, and threatens to shoot Alex and set her cats on him if he doesn't leave. After Alex breaks into her house, she fights with him, ordering her cats to join the melee, but reprimands Alex for fighting them off. She sustains a fatal blow to the head during the scuffle.

[edit]Analysis

[edit]Title

Burgess gave three possible origins for the title:

- That he had overheard the phrase "as queer as a clockwork orange" in a London pub in 1945 and assumed it was a Cockney expression.¹ In Clockwork Marmalade, an essay published in the Listener in 1972, he said that he had heard the phrase several times since that occasion. However, no other record of the expression being used before 1962 has ever appeared.[3] Kingsley Amis notes in his Memoirs (1991) that no trace of it appears in Eric Partridge'sDictionary of Historical Slang.

- His second explanation was that it was a pun on the Malay word orang, meaning "man." The novel contains no other Malay words or links.[3]

- In a prefatory note to A Clockwork Orange: A Play with Music, he wrote that the title was a metaphor for "...an organic entity, full of juice and sweetness and agreeable odour, being turned into a mechanism."[3]

In his essay, "Clockwork Oranges," ² Burgess asserts that "this title would be appropriate for a story about the application of Pavlovian or mechanical laws to an organism which, like a fruit, was capable of colour and sweetness." This title alludes to the protagonist's positively conditioned responses to feelings of evil which prevent the exercise of his free will. To reverse this conditioning, the protagonist is subjected to a technqique in which violent scenes displayed on screen, which he is forced to watch, are systematically paired with negative stimulation in the form of nausea and "feelings of terror" caused by an emetic medicine administered just before the presentation of the films.

[edit]Point of view

A Clockwork Orange is written using a narrative first-person singular perspective of a seemingly biased and unreliable narrator. The protagonist, Alex, never justifies his actions in the narration, giving a sense that he is somewhat sincere; a narrator who, as unlikeable as he may attempt to seem, evokes pity from the reader by telling of his unending suffering, and later through his realisation that the cycle will never end. Alex's perspective is effective in that the way that he describes events is easy to relate to, even if the situations themselves are not.

[edit]Use of slang

Main article: Nadsat

The book, narrated by Alex, contains many words in a slang argot which Burgess invented for the book, called Nadsat. It is a mix of modified Slavic words,rhyming slang, derived Russian (like baboochka), and words invented by Burgess himself. For instance, these terms have the following meanings in Nadsat:droog = friend; korova = cow; risp = shirt; golova ('gulliver') = head; malchick or malchickiwick = boy; soomka = sack or bag; Bog = God; khorosho ('horrorshow') = good; prestoopnick = criminal; rooka ('rooker') = hand; cal = crap; veck ('chelloveck') = man or guy; litso = face; malenky = little; and so on. Compare Polari.

One of Alex's doctors explains the language to a colleague as "odd bits of old rhyming slang; a bit of gypsy talk, too. But most of the roots are Slav propaganda.Subliminal penetration." Some words are not derived from anything, but merely easy to guess, e.g. 'in-out, in-out' or 'the old in-out' means sexual intercourse.Cutter, however, means 'money,' because 'cutter' rhymes with 'bread-and-butter'; this is rhyming slang, which is intended to be impenetrable to outsiders (especially eavesdropping policemen).

In the first edition of the book, no key was provided, and the reader was left to interpret the meaning from the context. In his appendix to the restored edition, Burgess explained that the slang would keep the book from seeming dated, and served to muffle "the raw response of pornography" from the acts of violence. Furthermore, in a novel where a form of brainwashing plays a role, the narrative itself brainwashes the reader into understanding Nadsat.[citation needed]

The term "ultraviolence," referring to excessive and/or unjustified violence, was coined by Burgess in the book, which includes the phrase "do the ultra-violent." The term's association with aesthetic violence has led to its use in the media.[4][5][6][7]

[edit]Author's dismissal

In 1985, Burgess published Flame into Being: The Life and Work of D. H. Lawrence, and while discussing Lady Chatterley's Lover in his biography, Burgess compared that novel's notoriety with A Clockwork Orange: "We all suffer from the popular desire to make the known notorious. The book I am best known for, or only known for, is a novel I am prepared to repudiate: written a quarter of a century ago, a jeu d'esprit knocked off for money in three weeks, it became known as the raw material for a film which seemed to glorify sex and violence. The film made it easy for readers of the book to misunderstand what it was about, and the misunderstanding will pursue me till I die. I should not have written the book because of this danger of misinterpretation, and the same may be said of Lawrence and Lady Chatterley's Lover. [8]

No comments:

Post a Comment